| Status | Personal property |

| Location | Kawasaki, Kanagawa |

| Site area | 309.41㎡ |

| Completion | 1965 |

| Design | Miho Haaguchi |

| Constructor | Shiraiwa Corporation |

| Structure | reinforced concrete & |

| Total floor | 241.6㎡ |

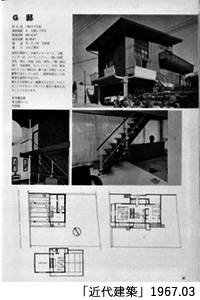

“My father, who has been to the Caucasus on Mount Everest region, asked Mrs. Hamaguchi to design this house as a mountain lodge. The house is characterized by large wooden framed windows on the north, south, east and west sides, a concrete veranda along the street, and a double-height living room where the family can gather”

(The eldest daughter of Mr. Nakamura)

G House (Former Nakamura House) by Miho Hamaguchii

The G House is a rare wonder to find. It was designed in 1965 by Miho Hamaguchi (1915-1988), a pioneer of modern Japanese architecture in many facets, at the height of her career. She is best known for her acute writings that influenced modern kitchen design, but her work goes far beyond. Hamaguchi's legacy is that of a bold residential architecture that embodied democratic ideas in spatial configurations. Although she designed and consulted thousands of houses throughout her prolific career, this is the only one known to exist, almost entirely in its original state. Thanks to high-quality design details and three generations of the Nakamura family who have lived and cared for this charming house, its architecture has weathered the test of time.

Miho Hamaguchi, a unique architect

At only 34, Miho Hamaguchi raised a new voice on the architectural scene with her groundbreaking book "The Feudalism of Japanese Houses" (Nihon jūtaku no hōkensei, 1949). In this text, she advocated non-hierarchical planning, focused on everyday life. She unraveled the feudal regimes of housing from history. She sought an egalitarian society without gender or class differences, and considered residential design as a tool to achieve this. This innovative perspective caught the attention of the Japan Housing Corporation, which asked for her collaboration to cope with the housing shortage after the war. Hamaguchi helped implement the "dining-kitchen" layout and introduced the stainless steel sink, a key component in modern housing.

At only 34, Miho Hamaguchi raised a new voice on the architectural scene with her groundbreaking book "The Feudalism of Japanese Houses" (Nihon jūtaku no hōkensei, 1949). In this text, she advocated non-hierarchical planning, focused on everyday life. She unraveled the feudal regimes of housing from history. She sought an egalitarian society without gender or class differences, and considered residential design as a tool to achieve this. This innovative perspective caught the attention of the Japan Housing Corporation, which asked for her collaboration to cope with the housing shortage after the war. Hamaguchi helped implement the "dining-kitchen" layout and introduced the stainless steel sink, a key component in modern housing.

Miho, the eldest daughter of the prosperous Hamada family, was born in Dalian, China. Upon returning to Japan, she studied Home Economics at Tokyo Women's Normal School, present-day Ochanomizu University. As female students were not allowed to enroll in the architecture department at Tokyo Imperial University officially, she attended classes as a listener. Through her determination, she became the first woman to be licensed as an architect in Japan in 1954, running her independent firm in Aoyama.

When G House was designed, there were ten employees at the office, and she worked closely with one staff per project. The architect who collaborated for G house was Yoshio Kanemaki, who recalls how Hamaguchi would draw repeatedly over the plans, constantly improving them. Miho Hamaguchi implemented a design that emphasizes living in terms of floor plan. Features of this house hint that Hamaguchi had worked with Kunio Maekawa for nearly a decade. The prominent curved concrete balconies of the facade, the rectangular proportions of the window frame, the materiality of the square tiles in the living room and the tiny ones in the bathroom, as well as the impressive double-height, can be read as possible influences.

Nakamura family and the mountain imaginary

Mr. Nakamura, a businessman and mountaineering enthusiast was the client of G House. His older sister was a friend of Miho Hamaguchi. When they moved into their newly built home, they were a family of six: grandparents, parents, and two little girls. Remarkably, Hamaguchi thought from the beginning that the house would grow with the family's needs. Initially, the third floor just had a single room for a young family and their daughter with a huge terrace. When the girls grew up Hamaguchi designed an extension with a folded origami ceiling which is fully integrated into the exterior volume. The gable roof is reminiscent of a hill, demonstrating a playfulness that is rare in suburban neighborhoods. Clear skies bring the Tanzawa mountain range and Mount Fuji as its background, to the remaining spacious veranda.

Mr. Nakamura fondness for the mountains, who even scaled the Himalayas, is evident in the alpine paintings and hiking tools that decorate the walls. The very appearance of the house is reminiscent of a mountain lodge owing to Hamaguchi successful combination of client request and modernism. A single flight of wooden stairs anchored to a couple of thin round steel pillars through the railing painted in off-white contrasts with the gleaming bluish-green of the tiles. These are custom-made, as are the mosaic ones in the bathroom, installed one by one by a tiler, becoming a distinctive feature of the G House. The staircase articulates the three levels, functioning as a lookout over the living room along with a small interior balcony. The eldest daughter of Mr. Nakamura remembers how her father joked that the magnificent staircase could serve as a jungle-gym for his children.

Design in every detail

Hamaguchi's brilliance begins with the selection of the site itself. When this residential area was developed in a formerly hilly scenery along the Tama River, Mr. Nakamura decided to buy a plot of land. They even started to draw some sketches when Hamaguchi herself checked the geological condition and decided to change to better grounds, the current location. She fitted the house into the terrain lifting it off the road with a concrete plinth and a piloti structure, leaving enough space for two cars. This modernist gesture is completed with a setback that creates a bright entrance hall. The elegant vestibule served as an ideal setting for short visits.

On ascending to the next floor, the lower level lobby expands in an explosion of color and light. The chandelier hangs in the middle of the double-height space in the same position as the original one. Materials such as wood, tile, and stucco combine in a textured and comfortable space. The interior environment was considered through the floor-to-ceiling windows, which allowed for cross ventilation, opening or closing automatically depending on wind pressure. Thanks to Hamaguchi's careful attention of circulation flows, no space is wasted in this house. The dining-kitchen takes on an important role, a central space connected to the living room, a bedroom for the grandparents, and a bathroom. The original kitchen furniture, designed by Hamaguchi, has two sinks and a large cutting area. The sequence of food from washing, cooking, and serving to the table is thought out in detail. A door neatly tucked into the wall, provides access to the wet area. In the past, liquor or rice sellers used to leave their deliveries at this access from the street, connecting the urban realm directly to the refrigerator.

Natural light permeates every corner. The characteristic deep eaves respond to the Japanese climate, protecting the vertical wood-clad facade. A cut in the beautiful curved balconies reveals the entire glass surface from the street. The south garden can be accessed directly from the second floor, creating a pleasant relationship with the outside environment. Here, roses exhale their fragrances in spring, and tsubakis dye the winter red. This house is material proof of Hamaguchi's avant-garde yet gentle architecture, in which she is mindful of the client's wishes and the inhabitants' lives. Its design quality makes it extremely valuable for its own story and for history. This is a truly magnificent house designed by a genuine architect.

Noemí Gómez Lobo (PhD Architect)

Kana Ueda (Architect)

(10 May, 2021)

Photos: Diego Martín Sánchez